Her father’s legacy… Her family’s shame…

A secret held by too many generations…

1936 Brought up in Cornwall by her grandparents, Aster thinks often of her parents, who were taken from her at a tragically early age. The only thing she has to remember her mother Violet by is her Flower Book, a journal of pressed flowers that charts Violet’s life and dreams – and keeps all her secrets...

On her 21st birthday, Aster receives devastating news that turns everything she knew about herself upside down. Will she finally discover what really happened to her parents?

First published in 2014 as The Flower Book

‘When my publishers Boldwood were preparing to re-release The Flower Book, I had the opportunity to read through it again. I soon realised that, in the ten years since I first wrote the book, my writing style had changed. I felt strongly that I wanted to rework it. In doing so, I replotted the story and tightened it up, and, in my opinion, improved it! The result is The Artist’s Daughter. I hope you enjoy.’ Catherine Law

The sketch by her father was in brown ink, dashed off hurriedly, Aster guessed, between roll call and stand-to.

At the bottom was his signature and one simple word, Hope.

My name means Hope, Aster thought. I am Hope.

The drawing was a portrait of a little girl.

Reviews for The Artist’s Daughter

“Sad and haunting… If Michael Morpurgo had written Tess of the d’Urbervilles, the result would have been something similar to The Artist’s Daughter.”

“I can’t even begin to describe the joys of her prose with its delightful evocative descriptions of the glorious countryside which clash vividly with the harsh scenes of the battlefields, the barbarism and destruction of World War One and the effects on those who returned, damaged in both body and mind.”

“The Artist’s Daughter is an extraordinary historical tale that kept me on the edge of my seat and eagerly turning the pages. It is a spellbinding historical novel packed with mesmerising drama, atmospheric period detail, heart-wrenching sorrow and compelling emotion.”

Between the lines

What inspired The Artist’s Daughter?

Collecting flowers, collecting memories

The spark for this story had its origins in the novel I wrote before it (The French Girl, set during the Second World War). As I was finishing this book, I took myself off down to Cornwall to a cottage on my own for a week, for peace and time to write.

My enchanting surroundings of ancient lanes, silent woods and hidden valleys eased my mind and got me thinking more about my character Marcus, (Nell’s father in The French Girl, who had fought in the Great War). It struck me how quickly one great conflict followed the other – only a matter of twenty years – and how men were still reliving the first as the second started. I simply had to explore the First World War.

For my new book, I decided to leave Marcus where he was, and create Jack Fairling. Like Marcus, Jack was an artist, and he communicated his time on the Front through his paintings and sketches (interpreted by David Bryant in the gallery above): Jack’s message home to his estranged love, Violet.

I also wanted to tap into Violet’s experience of the war: the long stretches of waiting-time during which all she could do was imagine, want to understand, and, naturally, misunderstand. How could she ever know Jack’s nightmare reality? This is exactly how I, as a writer, felt. So, next stop, an organised tour of the Western Front.

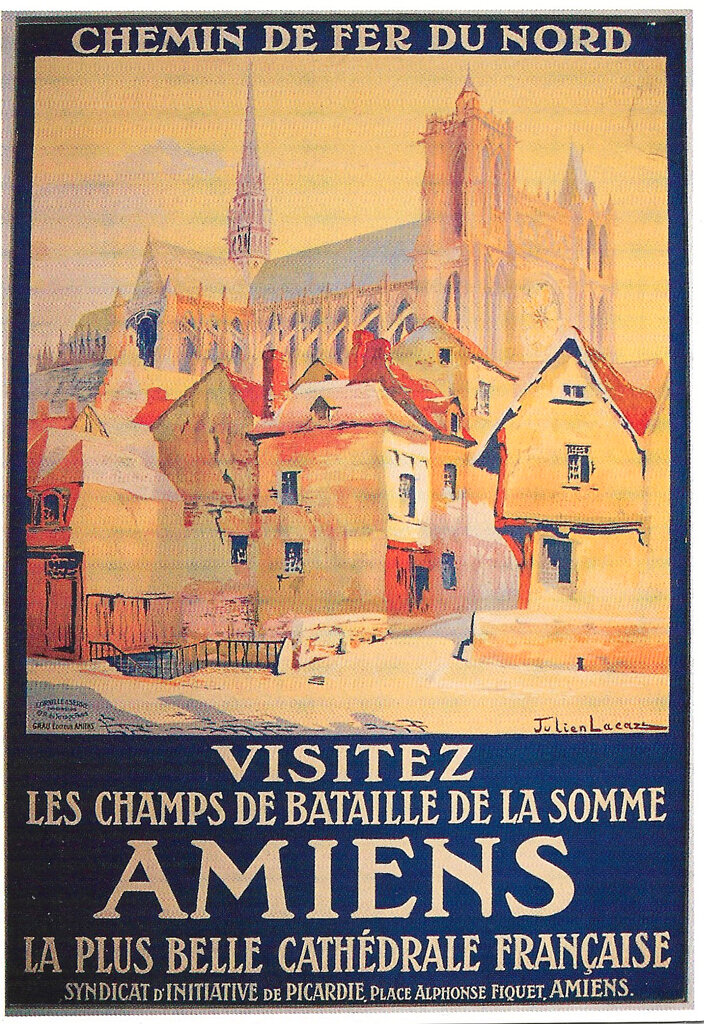

I had to see the remains of the trenches and battlefields myself, to somehow bear witness and to do this important subject justice. I needed to become emotionally involved in something I have no way of truly knowing. I spent most of the trip in tears. The shock I felt as each astonishing piece of information was imparted became physical. Seeing the sketches of German artist Otto Dix at the museum at Amiens finally floored me. I had to get across his brutal depiction of the trenches, to recreate the horror I felt. But to portray something so visceral and degrading, I had to counter it with the beauty and peace I experienced in Cornwall, and so I set my story there.

The novel opens in 1936 when, Aster, Violet’s daughter, discovers the mother she never knew through Violet’s book of pressed flowers. Aster delves into the memories passed back through the years, preserved in Violet’s own journal, and uncovers the story of Violet and Jack lost to time.

{My character Jack Fairling also appears in The Runaway, as the artist who paints the portrait of Beatrice, Carlotta and Alexa}